Welcome to spring. And with it, your new spring reading list – which sees a welcome return from some brilliant favourites (Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Natasha Brown among them), alongside a handful of truly fine debuts and other gems.

We have a prize-winning short story collection, a sharp, dark, funny look at London’s rental crisis, a One Day-style love letter to the noughties music scene and the first in a startling new (to English language reader) literary series that pushes that well-worn trope, the timeloop, into bold – even profound – new territory. And that’s only the start. So settle in – it’s going to be a thrilling ride.

Dream Count, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

The Americanah author returns with her first novel in 10 years. Opening into March 2020 just after the first wave of global lockdowns have been announced this is not, many will be pleased to know, a pandemic novel as such. Rather, Adichie uses the isolation and strangeness of that time as a framing device for lead character Chiamaka – a wealthy Nigerian-born travel writer who is based in the US – to look back on her life and relationships and ponder (in every sense) where next. Broken into four main narrative strands and voices: Chiamaka, her best friend, the housemaid she sees as ‘family’, and her closest cousin. Each one builds on the last, opening out the story, offering differing perspectives and insights into what we already know. It’s a rich, multistranded tale of women, relationships, motherhood and ambition that turns hot-topic issues around race, gender politics, FGM and sexual assault into profoundly moving personal insights, courtesy of its characters. In short, Dream Count lives up to both the anticipation and hype.

A Beautiful Lack of Consequence, Monika Radojevic

A collection of 30 short stories – some just a few pages long – from the winner of the Merky Books New Writers Prize. Radojevic is a poet and women’s rights activist and both her ear for the rhythm of language and the causes and frustrations that shape our times are present and correct in this funny, playful, irreverent, but always sharply on point examination of contemporary women’s lives. Subjects range from bodily autonomy to the price many women pay to navigate a so-called smoother path through life (‘She was born fierce, with a pair of wings, but somewhere along the way she sold them,’ Radojevic writes of her unnamed universal ‘girl’ in Blood Ridden) as well as joy: of friendship, self-discovery and the pleasures of falling genuinely, deeply in love.

A queer young writer who has so far failed to live up to his early creative potential (‘The world is at your feet, they said,’ he notes at one point. ‘I stamped all over it.’) is working a short-term contract as a creative writing tutor when he meets – and falls for ‘the poet’. The poet is older, highly esteemed – and a woman. While in theory, that should be able to be accommodated in the open relationship he shares with his handsome live-in boyfriend, Michael, their burgeoning friendship-slash-relationship threatens to undermine every part of all their lives. Throw in a homophobic mother and hidden family secrets and you could, on paper, have a recipe for something more salacious than sensitive, but Kelly is far too nuanced for that, crafting a tenderly written meditation on art, love and life that’s as much about the search for self as for connection.

I Want To Go Home But I’m Already There, Róisín Lanigan

Lanagan’s razor-sharp debut sees twentysomething couple Aine and Tom as they prepare to move in together, as much out of economic practicality as statement of relationship intent. They find a suspiciously cheap (though still barely affordable) flat in a pocket of the city with a 24-hour organic supermarket on the corner, but no decent transport links. Once they move in, however, things begin to change. A mysterious mould threatens Aine’s physical health, while an even more mysterious neighbour – the old man who lives in the flat upstairs – wreaks the same on her increasingly fragile mental state. Are we witnessing a ghost story or just another tale of the very real nightmare that is London’s rental culture? Lanagan’s genius rests in her ability to keep both narrative balls very much all in the air – with plenty of dark laughs along the way.

Universality, Natasha Brown

Brown’s debut, Assembly, heralded her as one of the brightest in Britain’s then emerging crop of young writers. This, her follow-up, sees Brown pushing the spare, tight narrative style of her debut in different directions. It opens with what’s quickly revealed to be an online article about a gold bar that was stolen from a Yorkshire farm that was squatted and shut down after hosting an illegal rave during lockdown. The article, penned by Hannah, a previously struggling freelance book reviewer, became a viral sensation, complete with a Netflix deal that has allowed Hannah to finally hook a big toe onto one of the lower rungs of London’s property market. But as the novel progresses and different characters move to the forefront – shock journalist Lenny and banker Richard among them – it becomes clear things are murkier than they first appear. If Brown’s satirical brush is a little broad at times, Universality remains a smart, thought-provoking and pacy read about class, capital (cultural and financial) and the general state of divided Britain today.

On the Calculation of Volume, Solvej Balle

We meet Tara on 18 November in the house of one Tomas Selter. Tomas, we quickly learn, is Tara’s husband, with whom she runs an antiquarian books business. Why she’s hiding from him in her own house, aware of every sound and move he’ll make before he makes it, takes a little longer to be revealed. Time, she tells us, ‘has fallen apart’. Tara has been caught in a timeloop since waking up in Paris – where she had travelled to on business – 121 days before. She’s not entirely stuck on repeat – a burn to her hand goes through stages from infection to healing; she is able to travel home to Tomas in rural France – but others are lost. Including Tomas’s memory, which resets each day.

As first the weeks, then the months, rack up, Tara’s hope of finding a way into the next day wears increasingly thin. But even as her plight deepens, she finds more and more to discover in the endless repetitive shape of a day lived over and over again. And it’s in here – as Tara finds more and more to discover in the endless repetitive shape of a day lived again and again, even as her plight deepens – where Balle moves away from the classic Groundhog Day conceit into something closer to transcendent and it remains gripping in every way.

In Balle’s native Denmark, where On the Calculation… is a literary sensation, five of the intended seven volumes in what will make up the complete series have been published so far. We have just Volume I and II in English for now – the first of which has, deservedly, earned Balle and translator Barbara J Haveland a spot on this year’s International Booker longlist. Is it too soon to ask for more?

Deep Cuts, Holly Brickley

One Day meets High Fidelity in Brickley’s sparky debut – two rather fitting vintage references for a Noughties-set novel about the music-obsessed wannabe writer Percy and budding musician Joe. We follow the will-they-won’t-they push and pull of their relationship from their musical meet cute at college (the pair bond over, of all things, a Hall & Oates song, which might be a litmus test too far) and through the next two decades of the new millennium. Their relationship – professional and personal – flounders as Joe becomes a bone fide rock star. The narrative deep cut that really drives the story, however, isn’t to do with the question of the pair’s attraction for one another, which it’s not spoiler to say is never really in doubt, but Percy’s own route to discovering herself and her talents.

Elegy, Southwest, Madeline Watts

Eloise and Lewis set off on a two-week journey through the American Southwest that’s part work (Eloise is an academic studying drying of the Colorado River; Lewis works for an art foundation that’s funding an epic piece of land art buried deep in the desert), part Great American Road Trip. The couple are young and in love but unlike the ever-depleting dams they visit in pursuit of Eloise’s research, the long-simmering undercurrents in their life and relationship threaten to break through the cracks and overflow as the journey continues. Watts makes it clear from the outset that all does not augur well – Lewis is grieving the death of his mother, Australian ex-pat Eloise is dealing with the question of whether she may or may not be pregnant; the pair become increasingly emotionally isolated from each other as a result of both. That she is able to not only foreshadow that so plausibly, but keep us guessing just what the fallout will be as she draws us to its inevitable conclusion, is a credit to her skills as a writer. Tender and hauntingly sad.

Elegy, Southwest, Madeline Watts

Eloise and Lewis set off on a two-week journey through the American Southwest that’s part work (Eloise is an academic studying drying of the Colorado River; Lewis works for an art foundation that’s funding an epic piece of land art buried deep in the desert), part Great American Road Trip. The couple are young and in love but unlike the ever-depleting dams they visit in pursuit of Eloise’s research, the long-simmering undercurrents in their life and relationship threaten to break through the cracks and overflow as the journey continues. Watts makes it clear from the outset that all does not augur well – Lewis is grieving the death of his mother, Australian ex-pat Eloise is dealing with the question of whether she may or may not be pregnant; the pair become increasingly emotionally isolated from each other as a result of both. That she is able to not only foreshadow that so plausibly, but keep us guessing just what the fallout will be as she draws us to its inevitable conclusion, is a credit to her skills as a writer. Tender and hauntingly sad.

Nine months’ pregnant Annie, is ‘milling in the crib section’ at IKEA in Portland, Oregon, fretting about the state of her finances, her career and her marriage when, seemingly out of nowhere, a monumental earthquake hits. She makes it out of the store alive with only one mission – to find her way to husband Dom. Over the course of the day that follows, Annie narrates their story to their unborn baby, Bean. We chart the path of their life together, from hopeful young artists (Annie was an aspiring playwright, Dom still aspires to become an actor) to disillusioned thirtysomethings struggling to make the even basic building blocks of modern American life work. In the process, Annie re-evaluates the ways to live a life. Pattee, a climate journalist by day who knows of what she speaks ((Portland lies smack bang in the heart of the very real Cascadia fault line, which has been estimated as having a one-in-three chance of triggering the Big One in the next 40 years), doesn’t shy from the horror of such a devastating event, but in Annie, she’s able to render it funny, tender and hopeful, as well as frightening.

Nobel laureate Gurnah’s first novel since he was awarded that very prestigious gong in 2021 is a multigenerational coming-of-age saga set in postcolonial Zanzibar and Tanzania that follows three characters from three very different backgrounds across several pivotal decades in both their own lives, and that of their country. Left to live with his grandparents after his mother flees the marriage to a much older man she was forced into, young Karim is determined he will do better. Early on, his fate is twinned with that of Badar, who moves into the household as a young servant boy. But as Karim’s star rises – he attends university, meets and marries his wife, Fauzia, the third major cog in this narrative wheel – Badar’s is thrown into disarray by an accusation that sets off a chain of events that, in time, changes all their lives irrevocably .

In many ways, Szalay’s charting of one man’s life from his youth in Hungary to adulthood in London and beyond serves as a sort of companion piece to his exceptional 2016 Booker-shortlisted novel-in-stories All That Man Is. It is, like that novel, told in a series of interlinked stories, but its focus on a single character, István, who we first meet as a teenager, heightens the sense of dislocation that has become something of a hallmark for Szalay. István is someone who moves through life as if it’s something that happens to him, rather than a person with any kind of agency. However shocking the things he encounters – and he encounters a lot, from sexual abuse and prison time to witnessing a friend die in his arms while serving in the Middle East – István soldiers on. He moves to London where his fortunes, largely guided by the whims and actions of others, continue to rise and fall until a single spectacular act lights the fuse that will blow his world apart. István’s story is not always an easy read, but it remains an enlightening and rewarding one.

All the Other Mothers Hate Me, Sarah Harman

Harman’s voice-driven debut is a fun, pacey, comedy-thriller in which ex-girlband singer and single-mom Flo will do anything – anything – to protect her beloved son 10-year-old Dylan. When one of his classmates – the heir to a fast-food empire and ‘little shit’ who has been terrorising Dylan at the posh west London school he attends suddenly and mysteriously disappears, that anything extends to doing whatever she can to prove her son, despite growing evidence to the contrary, is not responsible. All while trying to kickstart her dead-in-the-water singing career and fend off the threat of local serial killer, the Shepherd’s Bush Strangler. Enlisting the help of fellow expat Jenny, a lawyer whose no-nonsense approach serves as a great foil to Flo’s flakiness, she sets out to crack the case. As an American-in-(West) London herself, Harman has a great outsider’s eye for the various hierarchies and snobberies of the capital’s postcodes and class system. Very, very funny.

The Dream Hotel, Laila Lalami

Museum archivist Sara Hussein is returning home to LA from a work trip to London when she’s taken aside for questioning by security. We’re in a near-future US in which data from a sleep device designed to relieve insomnia, monitors your dreams and flags any propensity to commit future crimes is flagged to the state. Sara’s been having dreams that suggest she wants to do physical harm to her husband. She’s put in the Dream Hotel for further monitoring and like the Hotel California, once you’re in, it’s pretty much impossible to leave. Newly longlisted for this year’s Women’s Prize for Fiction, Lalami’s propulsive fifth novel is proof that the trend for dystopian fiction isn’t going anywhere.

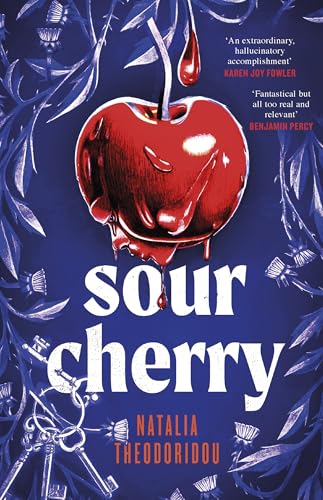

Sour Cherry, Natalia Theodoridou

Are monsters born or made? That’s one of the central questions underpinning Theodoridou’s dark, bloody retelling of Bluebeard – the story of the French nobleman and who killed his wives for disobeying a so-called simple trust exercise and kept their bloodied bodies in the basement of his castle for the next wife to discover in due course. As that suggests, this is not a light read. It is beautifully, poetically written. Rich, dense – and just a little relentless – this is one for fans of the new generation of dark, feminist body horror.